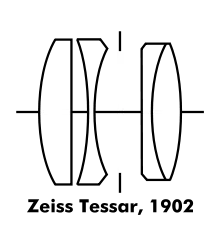

Among the many lens design configurations, one of the most common lens optical layouts is the Tessar Lens. This layout was created by Paul Rudolph in 1902 for photographic lenses. In the golden age of film photography, the Tessar configuration was widely used in common lenses such as the f 50mm/f2.8

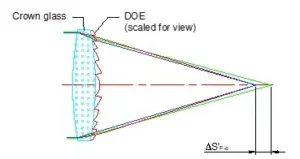

As with any photographic lens, the lens designers’ goal is to maximize image quality, which means removing as many aberrations as possible, especially reducing chromatic, spherical, and astigmatic aberrations. As mentioned in previous articles, one way to reduce chromatic aberration is by combining crown and flint glasses.

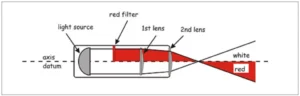

In a Tessar configuration, this is done by grouping four optical elements into three groups as shown in Figure 1.

The first optical element is usually a positive crown lens while the second one is a negative fling lens and a double achromat at the end. It is very similar to the Cooke’s triplet configuration: in the Cooke’s triplet, the rear lens is replaced by a single element lens. The last doublet helps further eliminate spherical aberrations.

When beginning the design of a Tessar lens, the best place to start is with the glass selection. For best results, the positive elements should be made of high-index crown glass. This helps to reduce the naturally negative Petzval sum and higher-order aberrations.

To reduce the three transverse aberrations (lateral color, coma, and distortion), a rule of thumb is to try to make the system as symmetrical about the stop as possible. Perfect symmetry is impossible because the object is at infinity and the stop is not exactly at the middle element. Nevertheless, the design still contains symmetry. This symmetry can help in deriving a starting configuration. In addition, a look at published Tessar layouts will suggest some useful initial constraints that can point the lens in the right direction.

Other starting points are:

- Make the inside surface of the front element flat.

- Make the two curvatures of the singlet negative element equal with opposite signs.

- Make the two curvatures of the positive element of the doublet equal with opposite signs.

- And make the front airspace equal to the space between the stop and the first surface of the cemented doublet.

There are more considerations in designing a lens, and many more when considering its optimization. In this blog, we have talked about achromatic design and optimization, correcting chromatic aberrations, and the steps for a “typical” lens design. So take a look at those and send us an email if you need assistance with your designing needs.

FAQs: Tessar Lens Design

What is a Tessar lens?

A Tessar is a classic photographic lens configuration originally developed in the early 1900s. It typically uses four optical elements arranged into three groups. The layout is known for delivering strong image quality with relatively low complexity compared to many modern multi-element camera lenses.

How is a Tessar lens arranged (elements and groups)?

A common Tessar layout uses a positive front element, a negative element near the middle, and a cemented doublet toward the rear. Grouping four elements into three groups allows designers to balance aberration correction while keeping the system compact.

Why did the Tessar become so popular in photography?

The Tessar offered a practical balance of sharpness, manufacturability, and cost. It provided good correction of key aberrations for common photographic use cases without requiring the large element counts that later high-performance lenses adopted.

How does a Tessar compare to a Cooke triplet?

A Cooke triplet uses three separate elements in three groups. A Tessar is often described as triplet-like but with an added cemented doublet toward the rear. That added degree of freedom helps improve correction, especially for spherical aberration and overall imaging performance.

Which aberrations does a Tessar design typically target?

Tessar designs commonly aim to reduce chromatic aberration, spherical aberration, and astigmatism while managing coma and distortion. The cemented doublet is a key tool for chromatic correction and can also help reduce higher-order aberrations when optimized carefully.

Why does crown and flint glass selection matter in a Tessar?

Chromatic aberration is reduced by combining glasses with different dispersion. Crown and flint pairings are a traditional approach for forming achromatic doublets. In Tessar-style designs, glass choice sets the baseline for chromatic correction before curvature optimization fine-tunes performance.

Why is symmetry around the stop mentioned as a design rule?

Making the system more symmetric around the aperture stop tends to reduce certain transverse aberrations such as lateral color, coma, and distortion. Perfect symmetry is not usually possible in real photographic configurations, but even partial symmetry can improve starting performance and make optimization easier.

What are practical “starting constraints” when building a Tessar?

Common starting constraints include flattening the inner surface of the front element, using equal-and-opposite curvatures for the negative singlet surfaces, using equal-and-opposite curvatures for the positive element in the rear doublet, and choosing reasonable airspaces that support symmetry and correction during early optimization.

What performance tradeoffs are typical with Tessar lenses?

Tessars can deliver strong central sharpness with moderate complexity, but may face limitations at very wide apertures, very wide fields, or when tight distortion control is required. Modern lenses often exceed Tessar performance by using more elements, aspheres, and advanced glass types.

When is a Tessar a good starting point for a modern custom lens?

A Tessar is a good starting point when a project needs a compact imaging lens with moderate field of view and a reasonable performance target. It is often useful as a baseline architecture that can be adapted through glass selection, spacing, and optimization constraints.

What information matters most if you want to adapt a Tessar to a real system?

The key inputs include sensor size, target field of view, wavelength band, f-number, working distance, chief ray angle constraints, and distortion/MTF requirements. These requirements determine whether a Tessar-like form is sufficient or whether a higher element count is needed.

What are common reasons a Tessar optimization “gets stuck”?

Common reasons include unrealistic requirements for the element count, too-aggressive f-number or field targets, and insufficient glass degrees of freedom. Optimization can also stall if stop location and symmetry constraints are not chosen thoughtfully, since those strongly influence coma and distortion behavior.